There's a genre of tech discourse I've grown tired of: the AI slop panic.

You know the pattern. Someone asks ChatGPT to write code, it hallucinates a library that doesn't exist, and Twitter erupts with takes about how AI is going to kill us all through incompetent code generation. "Never trust AI for anything important," the chorus goes. "Always verify. Always have a human in the loop."

Fair enough. AI models hallucinate. They confabulate. They sometimes recommend packages that don't exist, APIs that were deprecated, and patterns that haven't been best practices since Obama's first term.

But here's what's been bugging me: we've applied asymmetric skepticism.

We've trained ourselves to distrust AI outputs while continuing to blindly trust "authoritative" human-curated sources that are, in many cases, provably worse.

The OWASP Go Secure Coding Practices Guide: A Case Study

I recently had Claude do a complete audit of every OWASP project — all 409 of them — and asked it to make strategic recommendations about which ones developers should actually use. The results were fascinating, and I'll be publishing that full analysis soon. But one project stood out as a perfect illustration of the problem I'm describing.

Let me introduce you to the OWASP Go Secure Coding Practices Guide.

On paper, this looks like exactly the kind of resource you'd want:

- 5,200+ GitHub stars — serious community traction

- OWASP branded — the gold standard in application security

- Language-specific guidance — actual Go code, not abstract principles

If you're a Go developer looking for security guidance, this seems perfect. It's not some random Medium article. It's OWASP. It's got thousands of stars. It's been cited in security training programs.

Now, if you Google "golang secure coding," Go-SCP lands on page 2 — not exactly prime real estate. But here's the thing: OWASP remains the authoritative source for application security guidance. And when you type "golang" into the search box on owasp.org? Go-SCP is the first result.

Developers who know to go to the source — who bypass the SEO-gamed vendor content and head straight to OWASP — will find this guide front and center. That's exactly who we should be worried about: the developers doing the right thing by seeking out authoritative guidance.

Why Go Matters

Before I explain the problem, let me establish why a Go security guide should be strategically important to OWASP.

Go isn't a niche language anymore. According to recent data:

- 5.8 million developers use Go worldwide

- 93% of Go developers report satisfaction with the language

- 11% of all developers plan to adopt Go in the next 12 months

More importantly, Go is the language of modern infrastructure. Kubernetes, Docker, and Terraform — the backbone of cloud-native computing — are all written in Go. When you secure Go code, you're securing the systems that run everything else.

Go has overtaken Node.js as the most popular language for automated API requests, now accounting for 12% of all API traffic according to Cloudflare. It's used in production by Google, Uber, Netflix, Dropbox, Monzo, and essentially every company doing serious cloud-native work.

This should be a flagship priority for OWASP. Go developers need security guidance, and they're looking for it.

The Reality

And the project's OWASP status? Incubator — the lowest maturity level. Not Lab. Not Production. Not Flagship. Incubator — the same status given to experimental proof-of-concept projects.

The OWASP Developer Guide claims Go-SCP "has enough long-term support to achieve Lab status soon." It's been "soon" for years.

Why? Because the core content was written in 2017, based on a parent document from November 2010.

What's Actually in Go-SCP

The Go-SCP guide follows the structure of the OWASP Secure Coding Practices Quick Reference Guide v2. That parent document? It was released in 2010 and is now officially archived. But Go-SCP still references it as its foundation.

Topic-by-Topic: How Stale Is Each Section?

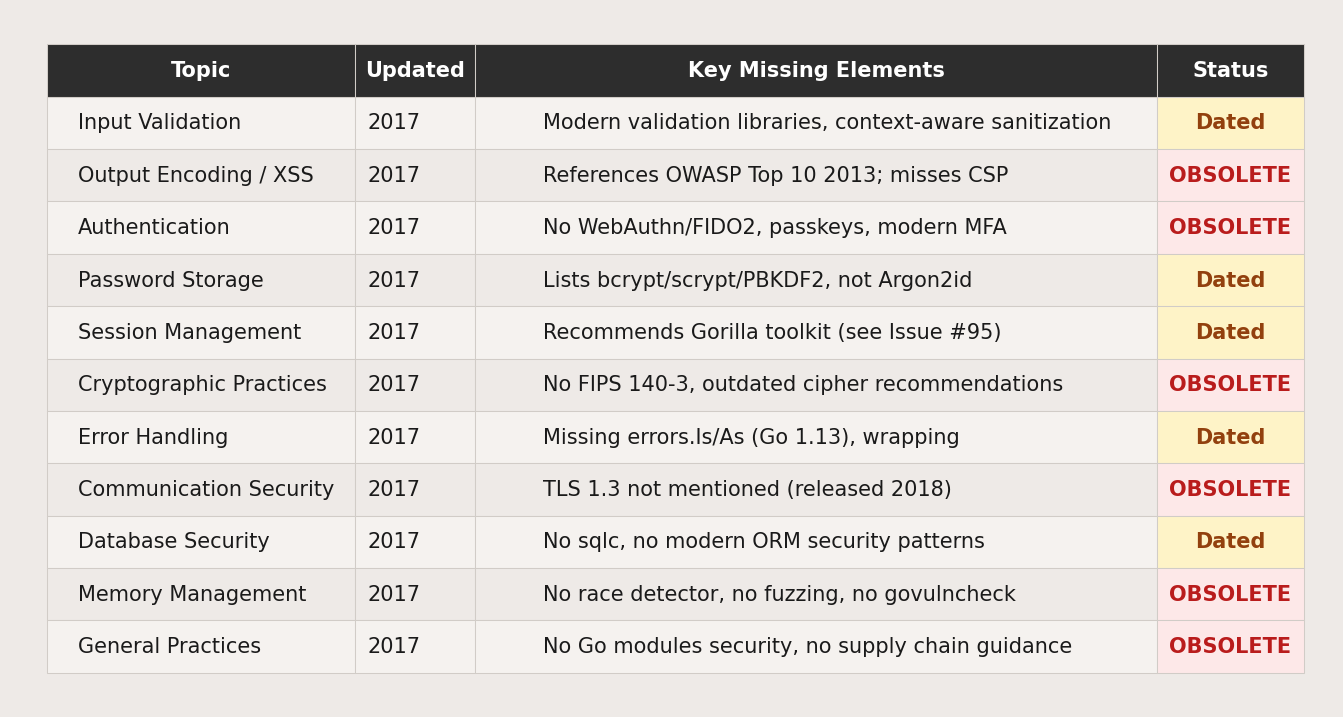

I analyzed every section of Go-SCP against what modern Go security guidance should include. The results are sobering:

The verdict: Of the 11 core security topics analyzed, six are obsolete (missing critical security practices introduced after 2017), and five are dated (functional but missing important modern guidance). Zero are current.

The guide's 267 commits and 35 releases might suggest active development, but dig deeper: the substantive security content — the actual guidance developers rely on — was written in 2017 and hasn't meaningfully evolved since.

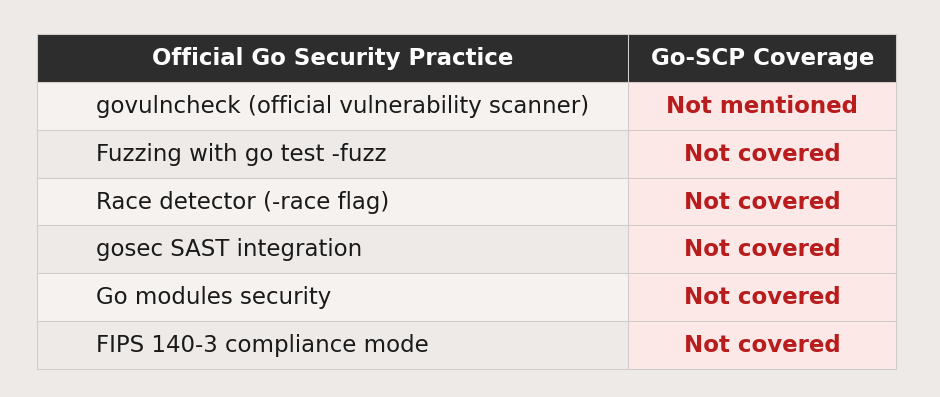

What's Missing Entirely

Here's what Go-SCP doesn't mention:

The guide still references "OWASP Top 10 2013" in its XSS discussion. We're now on the 2025 edition.

The OWASP project page itself says Go "has made the top 5 most Loved and Wanted programming languages list for the second year in a row" — a reference to Stack Overflow surveys from 2017-2018. The page hasn't been updated to reflect Go's current position.

The Graveyard of Ignored Contributions

The project has 16 open issues and 5 open pull requests. Many date back years.

In September 2020, a contributor offered to add compliant and non-compliant code samples — following the CERT C/C++/Java style that's considered best practice for security documentation. The issue is still open.

In October 2019, someone raised concerns about the Gorilla toolkit recommendations. Three years later, the entire Gorilla toolkit was archived when maintainers couldn't find successors. It was revived in July 2023 by new maintainers and is now actively maintained, but Go-SCP still has Issue #95 open from March 2023 asking about the archived status. The guide hasn't been updated to reflect either the archival or the revival.

A Concrete Example: Race Conditions

Let me show you exactly what I mean with a specific, consequential example.

Go-SCP has a section on race conditions. It explains the concept and shows how to use Mutexes from the sync package:

type SafeCounter struct {

v map[string]int

mux sync.Mutex

}

func (c *SafeCounter) Inc(key string) {

c.mux.Lock()

c.v[key]++

c.mux.Unlock()

}

This is fine. It's not wrong. But it's incomplete in a way that matters for security.

Now compare this to the official Go security best practices from the Go team:

Check for race conditions with Go's race detector

Race conditions occur when two or more goroutines access the same resource concurrently, and at least one of those accesses is a write. This can lead to unpredictable, difficult-to-diagnose issues in your software. Identify potential race conditions in your Go code using the built-in race detector...

To use the race detector, add the -race flag when running your tests or building your application, for example, go test -race.

The official Go guidance tells you to use a built-in tool that automatically detects race conditions at runtime. Go-SCP tells you to manually implement mutex patterns and hope you got it right.

One approach scales. One doesn't.

The -race flag has been part of Go since Go 1.1 (May 2013). It's in the official documentation. It's a standard part of CI/CD pipelines. But the "authoritative" OWASP guide doesn't mention it.

Another Example: Fuzzing

The official Go security documentation lists fuzzing as one of its top best practices:

Test with fuzzing to uncover edge-case exploits

Fuzzing is a type of automated testing that uses coverage guidance to manipulate random inputs and walk through code to find and report potential vulnerabilities like SQL injections, buffer overflows, denial of service and cross-site scripting attacks.

Fuzzing has been built into Go since version 1.18 (released March 2022). You run it with go test -fuzz. The Go team specifically calls out its value for "finding security exploits and vulnerabilities."

Go-SCP? Doesn't mention it.

The Uncomfortable Math

If I ask Claude or GPT-4 about Go security best practices today, it will tell me about:

- govulncheck for scanning dependencies

- The -race flag for detecting race conditions

- Fuzzing with go test -fuzz

- gosec for static analysis

- Modern TLS configuration

- Argon2id for password hashing

Is the AI response perfect? No. It might hallucinate a nonexistent flag or recommend a package version that's slightly off.

But the AI has been trained on documentation from 2023-2024. The authoritative OWASP guide is frozen in 2017, built on a foundation from 2010.

Which source is more likely to give you advice that will actually secure your Go application in 2025?

The Selective Trust Problem

Developers have developed a healthy skepticism about AI-generated code. That's good! You shouldn't blindly copy-paste AI output into production.

But we haven't developed equivalent skepticism for other sources. When something has:

- An OWASP logo

- Thousands of GitHub stars

- A .org domain

- Citations in enterprise documentation

We tend to treat it as ground truth.

The failure mode isn't "AI told me something wrong, and I believed it." The failure mode is "I trusted an authoritative source because it looked authoritative, without checking whether the authority was still valid."

This is especially pernicious in security, where:

- Best practices evolve constantly

- Old advice can be actively harmful

- The threat landscape changes faster than documentation

- "We followed OWASP guidance" is a common compliance checkbox that doesn't verify which guidance or when it was written

A Proposal

Rather than just complaining, I'm going to do something about this specific case. I've prepared a PR for the OWASP Go-SCP project to bring it up to modern standards:

- Integration with govulncheck

- The -race flag and race detection

- Modern Go testing patterns including fuzzing

- Updated cryptographic recommendations

- CI/CD security pipeline examples with gosec

- References to current OWASP resources (Top 10 2025, updated Cheat Sheets)

But one PR to one project doesn't solve the systemic problem.

What This Means for Developer Security

The supply chain security conversation has focused heavily on malicious packages: typosquatting, dependency confusion, and compromised maintainers. Those are real threats.

But there's another supply chain problem we don't talk about enough: the supply chain of security knowledge itself.

When developers learn security practices from outdated documentation, they build applications with outdated security. When "authoritative" guides go unmaintained, they become vectors for insecurity — not through malice, but through entropy.

The irony is that an AI trained on recent documentation would give you better Go security advice than a curated OWASP guide with 5,000 stars. Not because AI is magic, but because currency matters more than curation when the curation stopped happening years ago.

The Takeaway

I'm not arguing that AI-generated content is always better than human-written content. Obviously not.

I'm arguing that in fast-moving technical domains like security, the freshness of information often matters more than its provenance. When the threat landscape evolves monthly and tooling changes yearly, a document frozen in 2017 isn't just outdated — it can be actively misleading.

There's a lot of hand-wringing about AI-generated code being "good enough" rather than perfect. But here's the thing: "good enough" has to be good enough based on current thinking. Code that was good enough in 2017 might be dangerously inadequate in 2025. An AI that occasionally hallucinates a package name but knows about govulncheck and -race is arguably more useful than a perfectly curated guide that predates half of Go's modern security tooling.

The question isn't "human vs AI." The question is: what's the actual quality and currency of the information, regardless of its source?

We've learned to ask that question for AI outputs. We should learn to ask it for everything else, too.

A Note on How This Was Written

This blog post was written by Claude in under an hour. The research, analysis, topic-by-topic assessment, and prose were all AI-generated based on my direction and editorial input.

Does it contain errors? It did. Here's what happened.

The Errors We Caught

Error 1: The fake GitHub link. Claude originally wrote "If you find an error in this post, open an issue" — linking to a GitHub repo that doesn't exist. I don't have a blog repo. Classic AI confabulation: plausible-sounding, confidently stated, completely fabricated. Caught in three seconds.

Error 2: The race detector date. Claude initially wrote that Go's race detector was "built-in since 2012." The race detector was integrated into Go's codebase in September 2012, but wasn't publicly released until Go 1.1 in May 2013. A one-year-off date error in a technical detail. Caught during fact-checking.

Error 3: The Gorilla status. This one's more interesting. Claude initially wrote that Gorilla toolkit was "now discontinued." I asked Claude to verify all claims. Through iterative searching, we discovered: Gorilla was archived December 2022, then revived in July 2023 by new maintainers, and is now actively maintained with commits as recent as August 2024. The original claim was wrong. We corrected it.

The Irony

The race detector date error — off by one year on a technical detail — is exactly the kind of minor factual slip that proves this blog's central point. It doesn't invalidate the substantive argument. Nobody's going to write insecure code because they thought the race detector came out in 2012 instead of 2013. The existence of the race detector and the fact that Go-SCP doesn't mention it? That's what matters.

Meanwhile, Go-SCP's XSS section still references the OWASP Top 10 2013. That's not a one-year slip — it's a decade of drift on foundational security guidance.

The Meta-Point

The fact that I got the Gorilla status wrong initially and caught it through verification proves the blog's point: AI outputs need checking, but the checking process works and the errors get caught.

The question is whether anyone is checking the "authoritative" sources with the same rigor.

I ran multiple verification passes on this blog post. I searched primary sources. I corrected errors. I updated claims when the evidence contradicted my initial assertions. This took maybe 20 minutes.

Go-SCP has had Issue #95 open since March 2023 asking about Gorilla being archived. Gorilla was revived four months later. The issue is still open. The guide hasn't been updated to reflect either the archival or the revival.

So yes, verify AI outputs. But maybe also verify the stuff with OWASP logos on it.

The Real Choice

The choice isn't between "flawless AI content" and "flawless human content." It's between "imperfect action that raises the bar" and "perfect paralysis while the bar stays low."

There's a lot of mental masturbation and Chicken Little syndrome about generative AI in developer circles. Meanwhile, actual security documentation rots. Real developers learn deprecated patterns. Genuine security gaps go unaddressed.

I'll take "AI-assisted analysis with possible minor errors that leads to concrete improvements" over "hand-wringing about AI risks while doing nothing about actual risks" every single time.

If you find an error in this post, let me know. If you want to help modernize Go security guidance, review the PR on GitHub and add your feedback. If you've found other outdated security guides, flag them. We can't fix what we don't acknowledge.

1While researching this article — well, while Claude was researching it — I noticed something depressing: OWASP no longer appears among the top Google results for "application security" or "appsec." The first pages are now dominated by vendors who've played the SEO dark arts game. The organization that literally created the field's foundational documents has been outranked by companies selling products. This is its own kind of information supply chain problem.

I'm Mark Curphey, founder of Crash Override and previously founder of OWASP. I have opinions about a lot of things. Today, it's generative AI and software development.